Robin George Collingwood (February 22, 1889 – January 9, 1943) was a British philosopher and historian whose work has had considerable influence on modern historians. Collingwood is best known for his The Idea of History, a work collated soon after his death from various sources by his pupil, T. M. Knox. Collingwood held that history could not be studied in the same way as natural science, because the internal thought processes of historical persons could not be perceived with the physical senses, and because past historical events could not be directly observed. He suggested that a historian must "reconstruct" history by using "historical imagination" to "re-enact" the thought processes of historical persons, based on information and evidence from historical sources. He developed a methodology for treating historical sources, so that other historians could experience the same imaginative process. Collingwood also recommended that a historian "interrogate" his sources, corroborate statements, and be sensitive to his own biases when "reconstructing" a historical event.

Collingwood was also a serious archaeologist and an authority on Roman Britain. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Collingwood published several editions of The Archaeology of Roman Britain, a survey of Roman Britain, Roman Britain and the English Settlements (1936), and his contribution to Tenney Frank's Economic Survey of Ancient Rome (1937). Collingwood's principal contribution to aesthetics was The Principles of Art. He portrayed art as a necessary function of the human mind, and considered it collaborative, a collective and social activity. True art, he believed, created an "imaginary object" which could be shared by the artist with his public. In viewing art or listening to music, the audience imaginatively reconstructed the artist's creative thought. Collingwood contributed in diverse areas of philosophy, and his problematic is similar to that of Gadamer, despite their different approaches to philosophy, who developed hermeneutic phenomenology after Heidegger.

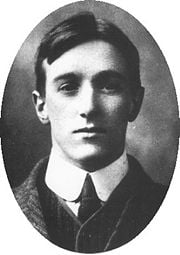

Life

R.G. Collingwood was born on February 22, 1889, in Cartmel Fell, Lancashire, at the southern tip of Windermere. His father, W.G. Collingwood, was an archaeologist, artist, professor of fine arts at Reading University, and acted as John Ruskin's private secretary in the final years of Ruskin's life; his mother was also an artist and a talented pianist. When Collingwood was two years old, his family moved to Lanehead, on the shore of Coniston Water, close to Ruskin's house at Brantwood.

Collingwood studied at home until he entered preparatory school at the age of thirteen. The next year he entered Rugby School, and in 1908, he went to University College, Oxford. He read Literae Humaniores and became a fellow of Pembroke College just before his graduation in 1912.

When he first began to study philosophy, Collingwood was influenced by the Oxford realists, including E.F. Carritt and John Cook Wilson. However, as a result of his friendship with J.A. Smith, Waynflete Professor of Metaphysical Philosophy from 1910 to 1935, he became interested in continental philosophy and the work of Benedetto Croce and Giovanni Gentile. In 1913, he published an English translation of Croce's The Philosophy of Giambattista Vico, and later he translated the works of Guido de Ruggiero, who became a close friend.

Much of Collingwood's own early work was in theology and the philosophy of religion. In 1916, he contributed an essay on "The Devil" to a published collection by the Cumnor Circle, a group of Church of England modernists, and published his first book, Religion and Philosophy. Collingwood was the only pupil of F. J. Haverfield to survive World War I.

Collingwood was also a serious archaeologist. Beginning in 1912, he spent his summers directing excavations of Roman sites in the north of England, and became an authority on the history of Roman Britain. He wrote hundreds of papers and several books on Roman archeol

ogy. At Oxford, he refused to specialize in either philosophy or history, taking an honors degree in both fields.

Late in 1919, Collingwood wrote a survey of the history of the ontological proof, together with an analysis of the argument, which he later developed in Faith and Reason (1928), An Essay on Philosophical Method (1933), and An Essay on Metaphysics (1940). In 1924, he wrote Speculum Mentis, a dialectic of the forms of experience: Art, religion, science, history, and philosophy. He also lectured on ethics, Roman history, the philosophy of history and aesthetics; Outlines of a Philosophy of Art, based on his lectures, was published in 1925.

Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Collingwood published several editions of The Archaeology of Roman Britain, a survey of Roman Britain; Roman Britain and the English Settlements (1936), and his contribution to Tenney Frank's Economic Survey of Ancient Rome (1937).

From 1928 onward, he also served as Delegate to the Clarendon Press, where his ability to read scholarly work in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Latin, and Greek was in great demand. The serious overwork began to take a toll on his health, which began to decline starting in the early 1930s.

In the autumn of 1932, he began writing An Essay on Philosophical Method (1933), an exploration of the nature of philosophical reasoning based on the introductions to his lectures on moral philosophy. He then began to concentrate on the philosophy of history and the philosophy of nature. The Idea of History (1946) and The Idea of Nature (1945), published posthum

ously, were taken from his lectures during this period. In 1935 Collingwood succeeded J.A. Smith as Waynflete Professor of Metaphysical Philosophy and moved from Pembroke to Magdalen College, delivering an inaugural lecture on The Historical Imagination in October of that year. In May 1936, he lectured on Human Nature and Human History to the British Academy. These two lectures were later included in The Idea of History. In 1937, he suffered a stroke while preparing The Principles of Art for publication. From then on, he knew that he had only a limited time to continue writing. An Autobiography (1939) announced his determination to record an account of the work he hoped to do but might not live to complete. During a voyage to the Dutch East Indies in 1938-9 he wrote An Essay on Metaphysics (1940) and began work on The Principles of History (not published until 1995). He also published The First Mate's Log (1940), an account of a Mediterranean yachting voyage around the Greek islands in the company of several Rhodes scholars from Oxford.

On his return to Oxford, he lectured on moral and political philosophy and began The New Leviathan (1942), his contribution to the war effort. As he wrote the book, he suffered a series of increasingly debilitating strokes. R.G. Collingwood died in Coniston in January 1943. He is buried in Coniston churchyard between his parents and John Ruskin. He was succeeded in the Waynflete Chair in 1945, by Gilbert Ryle.

Thought and works

Collingwood's thought was influenced by contemporary Italian Idealists Croce, Gentile, and de Ruggiero, the last of whom in particular was a close friend. Other important influences were Kant, Vico, F. H. Bradley, J. A. Smith, and Ruskin, who was a mentor to his father W. G. Collingwood, professor of fine arts at Reading University, also an important influence.

Collingwood is most famous for The Idea of History, a work collated soon after his death from various sources by his pupil, T. M. Knox. The book came to be a major inspiration for postwar philosophy of history in the English-speaking world. It is extensively cited in w

orks on historiography.

In aesthetics, Collingwood followed Croce in holding that any artwork is essentially an expression of emotion. His principal contribution to aesthetics was The Principles of Art. He portrayed art as a necessary function of the human mind, and considered it collaborative, a collective and social activity. True art, he believed, created an "imaginary object" which could be shared by the artist with his public. In viewing art or listening to music, the audience imaginatively reconstructed the artist's creative thought. Collingwood himself was an excellent musician.

In politics, Collingwood was a liberal (in a British, centrist sense), ready to defend an over-idealized image of nineteenth century liberal practice.

Historical imagination

Collingwood's historical methodology was a reaction to the positivist, or scientific, approach to the construction of knowledge which was in vogue at the end of the nineteenth century. Collingwood thought that the scientific method of observing phenomena, measuring, classifying, and generating laws based on those observations, was suitable for the natural world

but not for history. He argued that historical events had both an external and an internal aspect. The external aspect could be perceived using the physical senses, but the internal aspect, the thoughts and motivations of people involved in historical events, could not. In addition, historians were usually examining events which had occurred in the past, and did not exist substantially at the time they were being studied, as natural objects did. Since the historian could not actually observe events as they took place, Collingwood claimed that he must necessarily use his imagination to reconstruct and understand the past.

While imagination was usually associated with the fictitious, Collingwood argued that the imaginary is not necessarily unreal. Imagination was simply a process which humans use to construct or reconstruct pictures, ideas, or concepts in human minds. The historical imagination reconstructed pictures and concepts related to actions and thoughts that really occurred. A writer of fiction was free to imagine anything as long as his narrative had continuity and coherence. A historian had to use his imagination within the constraints of a specific time and place, and according to existing historical evidence. If a historian could not demonstrate that his ideas were consistent with historical evidence, those ideas would be regarded as mere fantasy. Without some kind of historical source, such as relics, written testimony or remains, to assist the imagination, a historian could not know anything about an event. Evidence from historical sources provided the grounds upon which a historian could imagine the past, and such evidence had to be referenced in a way that would allow others to "re-imagine" or construct the same ideas. Collingwood developed a methodology for the treatment of historical sources, such as documents and relics, as evidence to use in reconstructing the past.

Re-enactment

Collingwood called the process of using historical evidence to imagine and understand the past 're-enactment.' In order to understand past human actions, a historian must re-think the thoughts of the persons involved in that particular situation. The process involves examining relics and historical sites, reading documents related to an event, visualizing the situation as it was seen by the authors of the documents, and then thinking what the authors thought about dealing with the situation. By presenting themselves with the same information that was presented to a historical character involved in a past event, historians draw the same conclusions as the character. Collingwood held that historical understanding occurs when a historian undergoes the very same thought processes as the historical personage being studied, and that in some sense, "recollection" of past thought by a historian is the very same "thinking" as that of the historical personage. This doctrine is presented in the section of The Idea of History entitled, "History as the Recollection of Past Experience." Collingwood considered whether two different people can have the same thought process and not just the same thought content, writing that "there is no tenable theory of personal identity" preventing such a doctrine.

Simply reading and translating an author's written words does not necessarily convey the historical significance of those words and thoughts. Collingwood suggested two processes by which historians should go beyond the explicit information revealed in historical sources, "interpolating" and "interrogating."

Interpolating

Historical sources do not contain all the information necessary for a historian to understand a past event; therefore, the historian must interpolate between statements in a document, between what was said and what was implied, and between statements in different documents. Collingwood referred to this process of bridging gaps as "constructing history" and as an example of the use of historical imagination. Collingwood gave an example of historical sources telling about how Caesar was in Rome on one date and in Gaul on a later date. Though no mention is made of Caesar's journey to Gaul, the historian naturally imagines that the journey was made, though it is impossible to supply any further details without venturing into fiction.

Interrogating

Collingwood went further and suggested that historians could not accept the statements in historical documents without first evaluating them, using critical questions similar to those used by a lawyer interrogating a witness in court. The historian must take into account the biases of the document's author (and his own biases), corroborate statements with other historical evidence, and judge whether the evidence makes sense in the context of the historical construction being imagined. Ultimately, the entire web of a historical construction, including the pegs on which the strands are hung and the strands strung to fill the gaps, must be justified and verified by the historian's critical and imaginative mind. Collingwood employed these methods in his own historical work; his classic Roman Britain is an instructive example of his philosophy of history.

Adriana Trujillo

CI: 17863740

CRF

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario